CFD Case Studies: Exploring Airflow Dynamics in the Upper Airway

- Daniel Grafton

- Sep 16, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Sep 17, 2025

Disclaimer: This post is for educational purposes only. It is not a medical diagnosis or treatment. The findings discussed are part of a research case study and should not be used to make healthcare decisions. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for medical advice.

Introduction

In this post, we share results from two of our comparative case studies exploring how Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) can be applied to visualize and quantify airflow in the upper airway. If you are new to CFD, you may want to start with our CFD Primer before reading on. For a full overview of the past 20 years of CFD research applied to sleep-disordered breathing, please see CFD in Sleep-Disordered Breathing Research: Applications and Insights.

Case Study #1

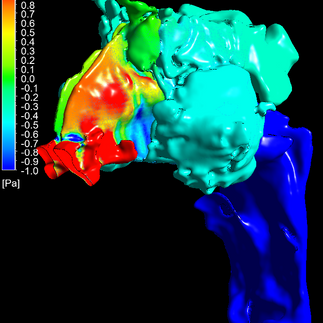

This first case study explores how maxillary expansion changed airflow dynamics in a patient who underwent expansion of their nasomaxillary complex. It compares airflow before and after expansion, using a series of CFD simulations. The images below help visualize how pressure and flow patterns shift dramatically with even modest anatomical changes.

Before Expansion: Pressure Concentration

In the pre-expansion model, CFD results highlight how airflow interacts with a narrow region at the nasal valve. High-pressure zones (shown in red and orange) cluster in this area, followed by a steep drop further into the nasal cavity.

This steep gradient reflects a point of resistance in the model, where air accelerates past constrictions and pressure rapidly decreases. The pattern provides a visual example of how bottlenecks can affect airflow distribution.

Figures 1–2. Pressure contours before expansion showing pressure buildups in the anterior nasal cavity followed by steep pressure gradients.

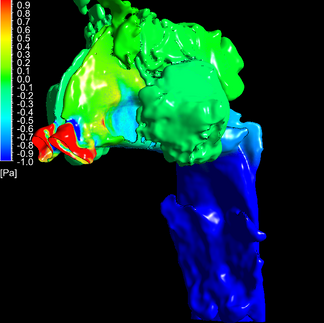

After Expansion: Pressure Distribution

In the post-expansion model, the overall pressure fields appear more gradual and evenly distributed. The colors shift progressively from green to blue, indicating smoother transitions within the nasal cavity.

Instead of sharp localized pressure drops, the gradients are spread across a longer section of the passage. This illustrates how structural changes can influence airflow pathways and resistance distribution in the model.

Figure 4–5. Pressure contours showing more even distribution of pressure after expansion

Case Study #2

This second study compares two individuals with sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) to a control subject without reported symptoms, examining whether CFD can highlight differences in airflow dynamics.

Findings

We focused on three key airflow indicators often discussed in airway research: pressure, velocity, and turbulence. Each offers complementary insight into airflow behavior.

1. Pressure

Inhalation creates negative pressure inside the airway. When this becomes sufficiently negative, the airway walls may be pulled inward. In CFD simulations, areas of steep pressure gradients often align with regions of narrowing.

Findings, from left to right:

Case 1 (Control): Stable airflow with few large pressure drops.

Case 2: Rapid pressure drop in the nasal cavity and oropharynx.

Case 3: Gradual pressure drop in the nasal cavity followed by a sharper drop in the nasopharynx.

These patterns illustrate how pressure distribution can vary between individuals.

We also compared average pressures across anterior and posterior slices of the nasal cavity. This showed different patterns of resistance distribution across cases, with variability in where pressure drops occurred.

2. Velocity

According to Bernoulli’s principle, airflow speeds up when passing through narrowed regions. In our models, velocity maps paralleled pressure findings, with higher speeds corresponding to tighter passages. This provides a visual way to explore where constrictions may influence flow.

Findings, from left to right:

Case 1 (Control): Some higher velocities observed in nasal cavity.

Case 2: Increased velocities in anterior nasal cavity and hypopharynx.

Case 3: Increased velocities in anterior nasal cavity and the upper pharyngeal airway, spanning from the naso- to the hypopharynx

3. Turbulence

Turbulence disrupts smooth (laminar) airflow, increasing resistance and energy loss.

Findings, from left to right:

Case 1: Predominantly laminar airflow.

Case 2: Mild turbulence in the oropharynx.

Case 3: More pronounced turbulence around the epiglottis.

Limitations

Like any modeling approach, CFD has constraints:

Steady-state assumption: These models simulate peak inhalation, not dynamic breathing cycles.

Static anatomy: Imaging captures a single posture and muscle tone; real-world airway behavior is more variable.

Standardized flow rate: Using a uniform airflow simplifies comparisons but doesn’t reflect individual physiology.

Future studies could address these issues through standardized imaging protocols, dynamic simulations, or larger sample sizes.

Discussion

Overall, CFD provided internally consistent results: pressure and velocity correlated as expected, and turbulence patterns aligned with areas of narrowing. This suggests CFD can serve as a physics-based, objective complement to more traditional, qualitative assessments of airway anatomy.

Importantly, these findings are illustrative. They show how CFD may help researchers investigate airflow behavior across different anatomical configurations. They are not diagnostic and should not be interpreted as treatment recommendations.

Looking ahead, with larger datasets and standardized protocols, CFD could contribute to research frameworks that explore relationships between airway structure, airflow patterns, and sleep outcomes.

Conclusion

These case studies illustrate how CFD can be used to compare airflow dynamics across and within individuals, highlighting differences in pressure, velocity, and turbulence. While CFD is not a clinical diagnostic tool, it offers valuable, physics-based insights for research and education.

As workflows improve and data accumulate, CFD may play an increasing role in helping researchers and clinicians better understand sleep-disordered breathing and its relationship to airway physiology.

Comments